SERIES: INTERVIEWS WITH PERFORMING MUSICIANS – Mike Marshall (Part 1 of 4)

November 7th, 2010 | Author: Vicki Ambinder

I am pleased to present the first installment of my four-part interview with multi-instrumentalist, world-touring musician, prolific record producer, and Adventure Music recording artist Mike Marshall. Mike began his illustrious career as a member of the original David Grisman Quintet, joining the band in 1978 at the age of 19. Since then, he has been one of the most innovative, respected, and well-traveled string players in the world of instrumental music, appearing on hundreds of recordings while expanding the horizons of American acoustic music to include many classical and international influences. Please see the bio on Mike’s website for more information on his remarkable achievements and collaborations. I spoke with Mike on September 20, 2010. This interview will be posted in four weekly installments. –VA

One of the reasons I really wanted to talk to you, Mike, is I love the way that you seem to just plug into the joy – it just seems to come spilling out of you. And I’m really curious to hear how you do that, or why you think that is. Where does it come from for you?

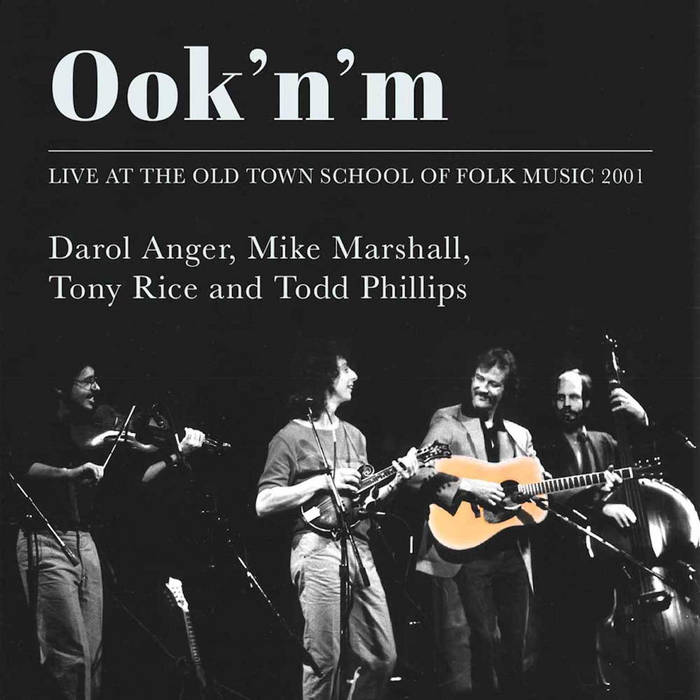

Mike Marshall: You know, I get people saying that quite often, and sometimes I’m not quite sure what they’re even talking about, because I’m just up there being myself. And, of course, I am overjoyed with all of the people I play with. I have a general feeling of amazing good fortune. You know, if I go down the list just this year, it’s pretty insane who I get to be onstage with. Darol Anger, Väsen, Paul Kowert, Alex Hargreaves, Edgar Meyer, Chris Thile – I mean, the list is kind of a who’s who of string music today. Real inventers, real creative people, but also people who really know the roots of the music that they came from. I forgot Danilo Brito, and Jovino Santos Neto. It’s kind of ridiculous, actually.

So there is that general feeling of joy to be living at the same time as some of these people. Everybody wonders what it would have been like to jam with Django Reinhardt, or to listen to J.S. Bach improvise, and most of the people I play with, I feel like I’m getting to have that kind of live experience. So that’s something to be pretty happy about, I think. And then there’s the added dimension of the audience, and their involvement.

How do you experience the audience? What does it feel like to you?

MM: You know, that part’s really easy – it comes very naturally to me. Maybe early on in my career I worried about whether the music I was playing was too intellectual for certain kinds of crowds, whether it be a festival where people are drinking and dancing in the dust, or a loud bar, where it might not be the optimal setting for the kind of music I’ve chosen to play. But over the years, I’ve realized that there’s a way to approach almost any live situation and embrace that crowd and that scene, and include them in what it is that you’re trying to get across, and still be 100 percent true to your artistic vision, but include them in the party. It’s really important to me that it happens.

Can you give me an example of how that comes about for you – where you’re being true to yourself but you’re letting the audience in?

MM: It might just be a simple introduction to a tune, because we play instrumental music – it’s like, what does it mean? You could name all of those tunes “Opus 1”, “Opus 2”, “Opus 3”, you know? But for whatever reason, we give them titles. If it’s “Borealis”, a tune I wrote with Darol, it has a story to go with it, and it hopefully helps people give them some visual reference. A historic thing about maybe where it was written or what it meant for us can be helpful, I think, to bridge that gap.

And then there’s during a song, where a great lick or a great break or something is going to amp things up for the audience and for you, where it’s going back and forth, the energy’s running in a cycle…

MM: Uh huh.

Are you one of those performers who’s in touch with that energy as it’s cycling through?

MM: Yeah, I mean, I feel like there’s two planes of reality going on almost simultaneously – two, or six, you know? But certainly there’s the whole issue of you being able to play your music, and play it as well as you can, and that whole internal struggle of trying to play something that’s difficult, or trying to push yourself improvisationally to another place, or trying to really be synched up with the musicians onstage and to be totally centered on the music.

At the same time there’s that dialogue going on with the audience and that energy that you’re talking about flowing back and forth. But one can be a distraction to the other, I find, and for me it’s about keeping a balance between those two trains running that are both running simultaneously in the same direction. If you get yourself too caught up in the audience and the feeling of what’s going on with them and me, and how do I look, you can miss a beat, right? You can get too distracted from what you’re there to do. At the same token, if you get too self-absorbed in your little world and you’re staring at your navel, the you’re not really in the room with all those people, and they came there to be with you. So I’m conscious of both things.

How do you keep focus? I know that’s a struggle for a lot of people, to learn how to put the focus where it needs to be. Is that something that gets easier with a lot of experience, or is that something that you’ve always had?

MM: It’s something I’ve had to a certain degree, but it can come in and out of focus, depending on the situation. If I’m playing something that’s really difficult, for instance – I tend to play a lot of challenging music, so this is an area where you have to be really careful of nerves, and conscious of them, to be alert enough to play what you’re there to play, but not so freaked out that you freeze yourself. So a lot of it has to do with who I’m playing with. There are certain kinds of musical collaborations that are just like water – I mean, it just flows, and there’s just no “work” feeling to it.

Like you and Darol, for instance?

MM: Yeah, well, that’s a funny one, because we’re really good at a certain kind of playing, especially improvising together – we can do that really well. But, I have to say that when we play as a duo, and I’m 50 percent of the sound, and you just have a mandolin and a fiddle, we have to work really hard, and be super-focused on that music to pull that off. Whereas, playing with Väsen is like being thrown into a river that’s flowing, and there’s so much other water around you that’s carrying you that if you just stand up there and hardly play anything, it’s fine, you know? You’re not going to screw that up.

When did you feel that you were at a level to play on the national stage? How did you come to that realization, or was that kind of a gradual thing?

MM: It was gradual, but it ramped up rather quickly. I started taking guitar lessons when I was 12 from a local guy down the street who played all the different string instruments – this was in Florida – and he also played a lot of different styles, just played all of them a little bit. He wasn’t a heavy virtuoso, but he was a great teacher. And I’ve always been grateful to him – his name was Jim Hilligoss – for kind of just pointing me at a whole bunch of musical plates. And he had me reading out of the Alfred’s Basic Guitar Methods, and saying the names of the notes and counting out the time and studying music theory.

But at the same time, he started a bluegrass band, and had me playing bass and mandolin and banjo and fiddle, and playing by ear, and going to jam sessions with real Southern old-time musicians – country musicians who would have Saturday night jams at their house. So I sort of got both sides of music training going, simultaneously, early on. And we all started a little teenage bluegrass band at that time, called The Sunshine Bluegrass Boys – we had peach-colored double-knit suits and a Winnebago with our name painted on the side of it.

Hey, a Winnebago, huh? Nice!

MM: We would go to these festivals all over Florida and Georgia and enter the contests, or eventually we were getting hired to play. And that was the early ‘70s, when the Osborne Brothers, and Jim and Jesse, and The Lewis Family – all these bands were playing festivals, and there was endless jamming all weekend long. So I just sort of got thrown into this whirlwind of Southern music, even though I wasn’t from the South. But that was a very exciting time, because you had Tony Rice and J.D. Crowe and groups like The New Grass Revival were just forming – the second generation – and The Country Gentlemen, who were pretty modern at that time, and lots of experimenting going on in the music scene. And I just got really swept up in the whirlwind of the excitement of traditional music but also something super-creative going on.

I’ve been reading the new Tony Rice biography [Still Inside: The Tony Rice Story, by Tim Stafford and Caroline Wright], and it describes how you basically showed up at his door and said, “I want to play music with you,” and he took you in. And I was thinking, certainly the music was new and changing direction, but it seems that the performance style was as well – what you were doing on the stage – not just the music.

MM: Yeah, everything about it was shifting. The best example I have is the first New Grass Revival album cover.

Oh, sure, yeah.

MM: It kind of says it all, you know? It was the ‘60s – it just sort of blasted into traditional music with the force of a nuclear explosion. And it sent a whole bunch of people back in time, studying the roots of the music, and you end up with a Bruce Molsky. And it sent a whole bunch of other people kind of out into the stratosphere saying, “Wait a second, I come from this tradition, but what is jazz? And how does that relate to this? And what is Indian music, and what is improvisation, based on where I am and what my tradition is? How do I stay true to my tradition and yet push at these boundaries?”

And when you think about how it’s presented on the stage, you’re going away from this sort of stilted, stand-in-one-place presentation.

MM: Yeah, gone are the matching outfits! So it’s a political statement as much as a social statement. You’re connecting with a different kind of audience. I went out to the West Coast, and San Francisco was such a hip place. And here were these guys just kind of holed up in a house in Marin County, working on their intricate, crazy new music – all day long, eight hours a day, just playing together. It was a real sort of West Coast “Big Pink”. [Note: Big Pink was the house in West Saugerties, New York that was shared by The Band members Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson, where The Band prepared to record their debut album, Music from Big Pink.] They worked for a year before they cut their first record, you know? So, yeah, it was maybe connected somehow to the whole West Coast psychodelia and Grateful Dead scene, in that you just walked onstage in a t-shirt and whatever you were wearing that day.

And the way you were onstage, too?

MM: Yeah, you know, it was Grisman with his antics – a crazy wild man with a beard who moved all over the stage. Tony Rice was always the antidote to that – stood stiff like a pillar. But I’ve come to realize now that if you’re playing the guitar, the acoustic Martin guitar, you kind of have to do that – especially the way he plays it. But the focus was on the music – it wasn’t really about presenting a show in terms of acrobatics.

What do you think about the school of thought that if you make a big show of looking like you’re working really hard, then the audience is going to think you’re doing more amazing stuff than if you make it look easy?

MM: Well, that’s true and not true. I can really see both sides of that, because when I think about Tony Rice at one of these festivals, getting up and playing his “Shenandoah” or something…

…and he’s just standing there…

MM: …he’s just standing there, and people do end up just going out of their minds. Because there’s so much that goes into this question of performance, because people are referencing off of their memories, when they’re hearing a band, as much as their eyes. And so sometimes you just walk on the stage and people applaud, because they’re so happy to see you. They’re happy that that performer is finally in their town. And as soon as he opens his mouth and you hear the sound of that music, then you’re just swept into that world. Because of the recording thing, you’ve spent all this time with those CDs, and now you’re really hearing it live, and it’s a little bit different but you’re totally focused on it. And I think as a recording artist, after you get a lot of years behind you, you’re really at a different kind of advantage than an upcoming performer who’s just getting started with that.

You’ve got some built-in “cred” that comes with you when you walk out there.

MM: Yeah, you hear Pete Rowan sing, and it’s so Pete.

He’ll talk about Bill Monroe…

MM: Here comes Bill, here comes that song that you’ve heard a million times…

…“Walls of Time”…

MM: …and it’s totally cool! That’s exactly why you’re there. So does he have to jump around to get your attention? No. He’s just standing there being Pete. Or Tim O’Brien – god, just hear him sing one note, and you’re, like, that’s why I’m here. And so this question of performing for the audience – I think that our generation, in fact, of those new acoustic pickers who decided to not wear the matching polyester suits anymore, like the ‘60s generation, kind of thumbed their nose at that whole idea of jumping around, creating anything that had to do with a Las Vegas-type show.

Have you noticed, though, in the newest generation, there is quite a bit of that going on?

MM: Yeah, things are shifting now! And the focus has changed. Since the post-Grateful Dead times, there’s now a need to fill that void that the Dead left. And that’s a different thing – that’s a party. As a band, you are in charge of creating the event that’s really a dance. It’s, get those people up and jumping and get them dancing. I’m thinking Yonder Mountain [String Band] and String Cheese [Incident], that generation of rootsy musicians. And that event calls for a whole bunch of things. First of all, it calls for volume – you have got to be loud. And so on go all the pickups.

So we’re talking about two different needs, different kinds of entertainment events. One is the people are actually there to sit quietly and listen, and it’s a little closer to classical music or jazz, or even old-timey music and bluegrass the way it was. And the other is a holiday – it’s a giant event, and it’s a party such that people are prepared to really jump around. And so as a performer, the demands on you are very different in each of those situations.

To be continued…